Here I collect glimpses of artworks that have crossed my path — encounters in museums, galleries, or unexpected places. These images and short notes trace the thoughts that art sparks in me. All rights to the images belong to the artists. I see this space as an open dialogue, an invitation to exchange impressions and ideas; feel free to reach out if something here speaks to you.

A work by Sara Ouhaddou shown at the Institut des Cultures d’Islam in Paris. The artist often collaborates with artisans from around the world, especially in Morocco. This piece belongs to a series in which she experiments with glass to create suspended sculptures and objects. The light passing through the colored details projects reflections and hues across the space, shaping a fragile and suspended atmosphere.

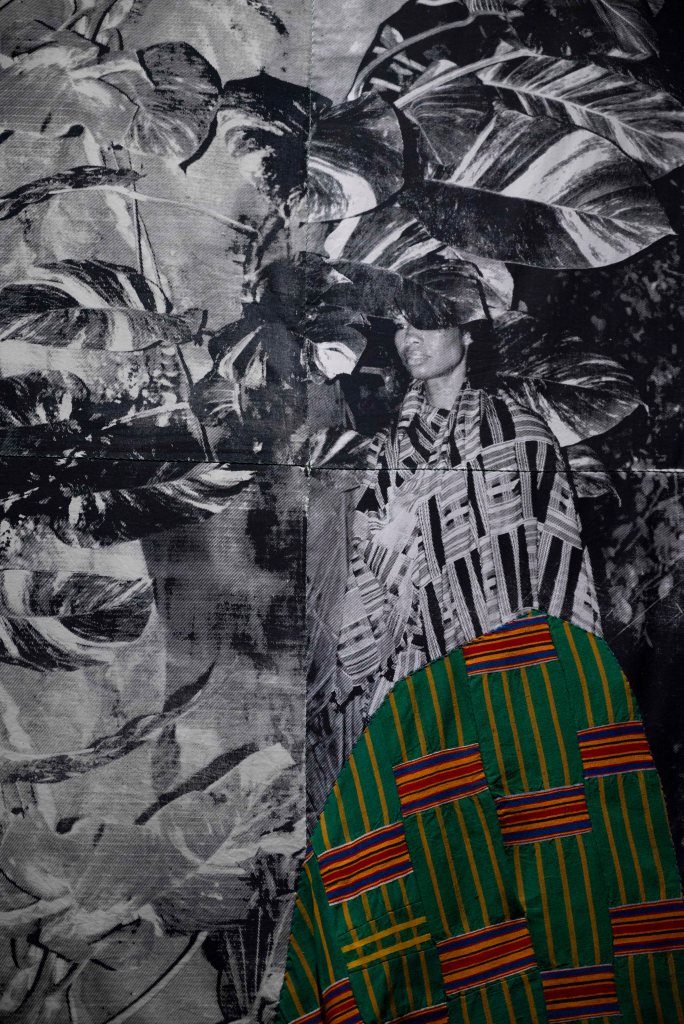

A detail from a work by Zohra Opoku, seen at the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town. The artist masterfully combines photographic printing on canvas, silkscreen, and textile techniques. Opoku weaves together symbols from different cultures and places, creating unique collages where materials and forms meet in delicate, experimental harmony, while exploring the layered histories of her Ghanaian and German heritage.

A detail from an installation by Thao Nguyen Phan, shown at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. The artist paints delicate watercolours over pages from a book by a French missionary who once worked in Vietnam. These images, at once tender and powerful, evoke dreamlike scenes and captivating figures. By layering her work over colonial narratives, Phan reclaims and reimagines local histories with poetic and political force.

This small painting by Paul Klee is one of the works from the Louvre Abu Dhabi collection that struck me the most. In its apparent simplicity, it brings together a constellation of carefully balanced elements: palm trees, a pyramid, a woman walking away in the lower left corner. Above all, the interplay of colored rectangles beautifully conveys the warmth and earthy tones Klee experienced during his journey to Tunisia in 1914.

The works of Jumana Emil Abboud consistently weave in fairy-tale elements, drawing deeply on folklore, particularly from Palestine. In an exhibition in early 2026 at the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, the artist brought together the results of years of research, tracing parallels and resonances between Palestinian and Japanese folklore. One of the most striking rooms was dedicated to glass works, like those shown here, in which Abboud revisits mythological sea-serpent figures that appear in both Palestinian and Japanese traditions.

One of the most compelling art districts in Dubai is Al Quoz, where former warehouses now host a vibrant network of galleries. At Efie Gallery, I discovered the work of Ethiopian artist Aïda Muluneh, whose practice merges photography and painting, blending figurative and abstract elements. Choosing a single work was difficult, but this image—where the portrayed woman removes her own face to reveal a galaxy beneath—struck me as particularly powerful and evocative.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres devoted many works to the poet Ossian, the mythical bard of Scottish legend whose very existence remains a matter of debate. In this drawing—combining pen, watercolour, and pencil—Ingres depicts Ossian asleep, a work I encountered in an exhibition dedicated to the theme of sleep in art history. The poet dozes off leaning against his harp. I love how the figures of the pantheon watching over him remain uncoloured, while the red of Ossian’s garment harmonises beautifully with the deep blue of the night sky, enriched by the subtle gradations Ingres achieves through watercolour.

At the National Gallery in London, I saw an entire room dedicated to the young Emirati photographer Farah Al Qasimi. The display was remarkable, filled with portraits of people concealed in various ways. In this photograph, we see a man in a living room, obscured by a cloud of smoke—his figure and the smoke merging into a single white mass within an otherwise heavily decorated interior. I was also struck by the painting hanging above the sofa, whose origin is unclear. The composition is excellent, especially with the presence of a woman’s hand reaching toward the man.

I love the story of the Carracci brothers and their art academy in seventeenth-century Bologna. This small painting of the Marriage of the Virgin strikes me as extraordinary—both in its composition and especially in the way the faces are rendered. They are oval, with large, arresting eyes. I find myself wondering about the reason behind this distinctive stylistic choice, particularly in the female figures standing behind Mary and in the child in the lower left corner of the foreground.

Inspired by the unique geopolitical status of Antarctica — a land belonging to no nation, shared for scientific collaboration — Lucy and Jorge Orta imagine a utopian space of coexistence. Their installation, Antarctic Village – No Borders, Dome Dwellings (as seen at an exhibition at Palais de la Porte Dorée, Paris), features dome-shaped tents covered with flags and clothes from around the world, symbolizing unity and diversity intertwined. The work evokes the spirit of adventure and human encounter, envisioning an ideal village where borders dissolve and people gather.

Yinka Shonibare, Archive of Lost Memories V, 2025 Seen at Art Basel Paris 2025 — perhaps the most commercial stage in the art world — this work by Yinka Shonibare felt strikingly out of place, and deeply moving. It evokes the struggle for colonial restitution and the fragile construction of memory. Displayed in a space driven by ownership and exchange, the piece becomes almost ironic: a fictional archive of lost histories presented where cultural objects are most often uprooted and traded. One can’t help but wonder whether, in time, this very archive might be fragmented and sold — a new symbol of the ongoing challenges of preserving memory in postcolonial contexts.

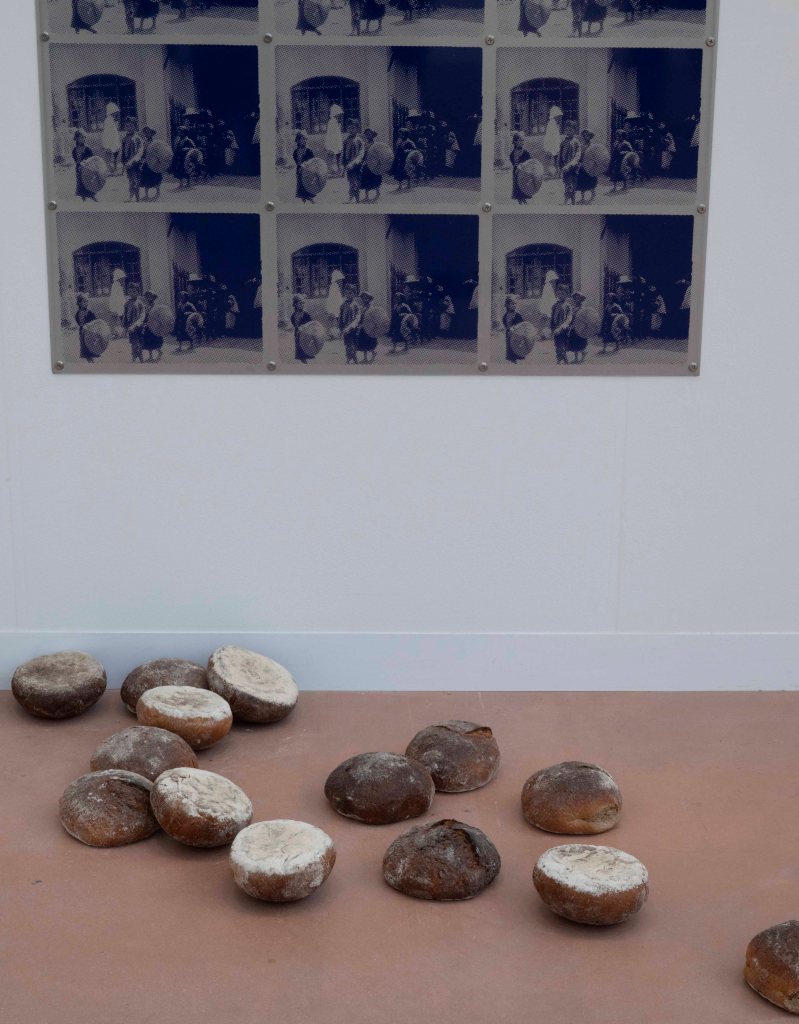

Sung Tieu. Also seen at Art Basel Paris 2025, this double installation by Vietnamese artist Sung Tieu was presented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery — one of the most compelling presences at the fair. The artist takes bread, a food introduced to Vietnam during colonization, and fills it with rice glue. Scattered across the gallery floor, these altered loaves seem almost to trip visitors, confronting them physically. The work questions the durability of materials and symbolically subverts a colonial element, reappropriating it through the integration of rice — a quiet but powerful gesture of cultural reclamation. Yet the artist’s intervention remains invisible: at first glance, they appear as ordinary loaves of bread. The transformation lies within — a metaphor, perhaps, for how the process of decolonization begins with inner awareness.

Lygia Pape was a leading figure of the Concrete art movement in Brazil during the 1950s and 60s. It’s fascinating to see how she evolved from creating small, simple geometric forms to large-scale installations like this one — while preserving the same poetic intensity of a single gesture. Here, she weaves golden threads that run parallel to each other without ever crossing, except in perspective. Set in a dark room and illuminated by light, they generate an extraordinary radiance and a suspended, almost magical atmosphere.

Gerhard Richter has gone through countless phases throughout his career, constantly reinventing himself and never repeating his own style. Yet, painting has always remained a constant in his practice — along with his unmistakable ability to merge blurred and sharp imagery. In this work, we see a deer, whose blurred form gives the impression of movement, as if caught by a camera in motion. It stands amid branches rendered with confident, stylized lines, perfectly still — a masterful contrast between motion and stillness within the same composition.

It’s fascinating how an Italian painter like Francesco Primaticcio ended up in France. This fresco, located in the ballroom of the Château de Fontainebleau, was commissioned by Francis I, who invited the artist to decorate the palace. I can almost imagine his journey across sixteenth-century Europe to reach this castle under construction, hidden in the forest. Among the many frescoes there, this one — almost discreetly placed — depicts Ceres riding her chariot drawn by two dragons. Her pose echoes the nude figures of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, which, through Italian Mannerism, found their way into France roughly a decade after Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

A detail from Corpario, a work by Mena Guerrero, shown at the Fondation Fiminco. Mixing influences from Egyptian aesthetics and Guatemalan-Maya vernacular culture, Guerrero’s ceramics covered the walls and filled the space with their vivid glazes and striking colour contrasts. In the industrial setting of Pantin, the bright tones stood out even more sharply against the grey concrete of the former factory.

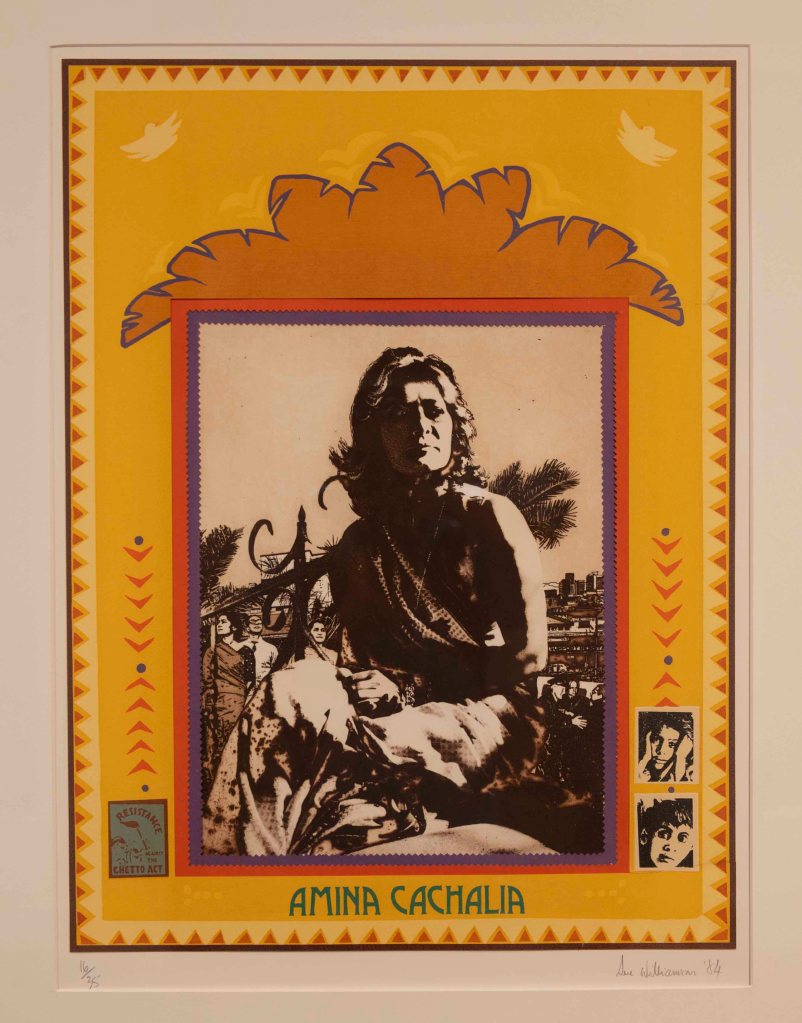

A work from Sue Williamson’s series A Few South Africans, shown at Cape Town’s National gallery in 2025. Photo-etching and screenprint collage. The portrait depicts Amina Cachalia (1930-2013), a lifelong anti-apartheid and women’s rights activist. The chiaroscuro shaping her face emphasizes her proud, steady gaze—one that seems to look beyond the frame, searching toward a brighter future for South Africa.

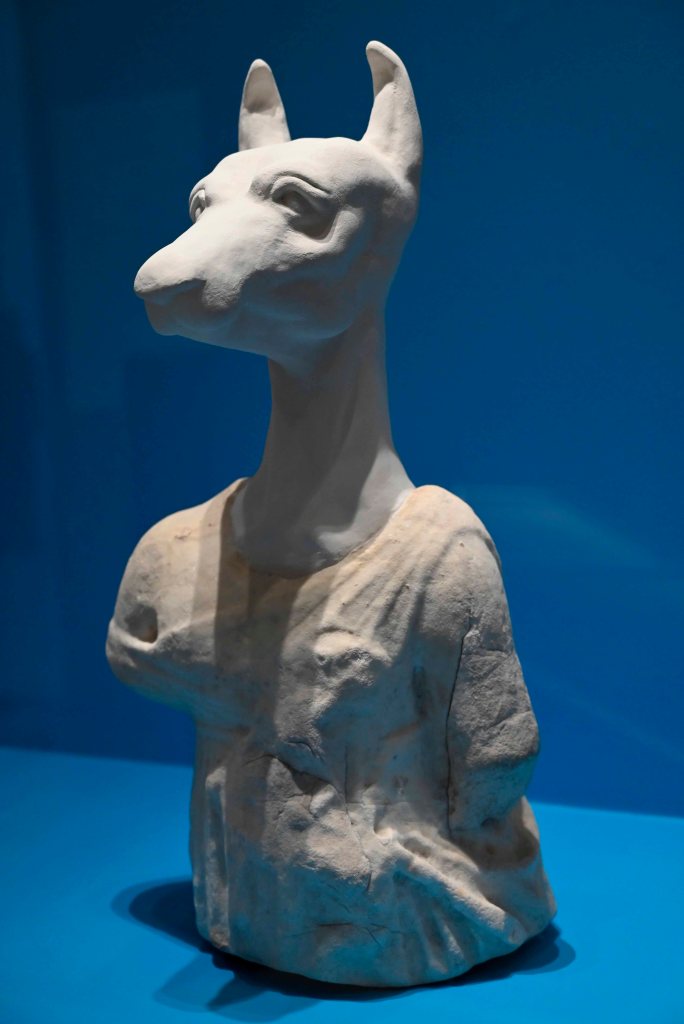

One of the works by Ali Cherri exhibited at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection in Paris in 2025. A hybrid figure—an Egyptian-like deity combined with the bust of an ancient Roman sculpture—inviting the viewer into a space of imagination and myth. The sculpture’s pure white stands out sharply against the blue backdrop, heightening the work’s contrast and timeless resonance.

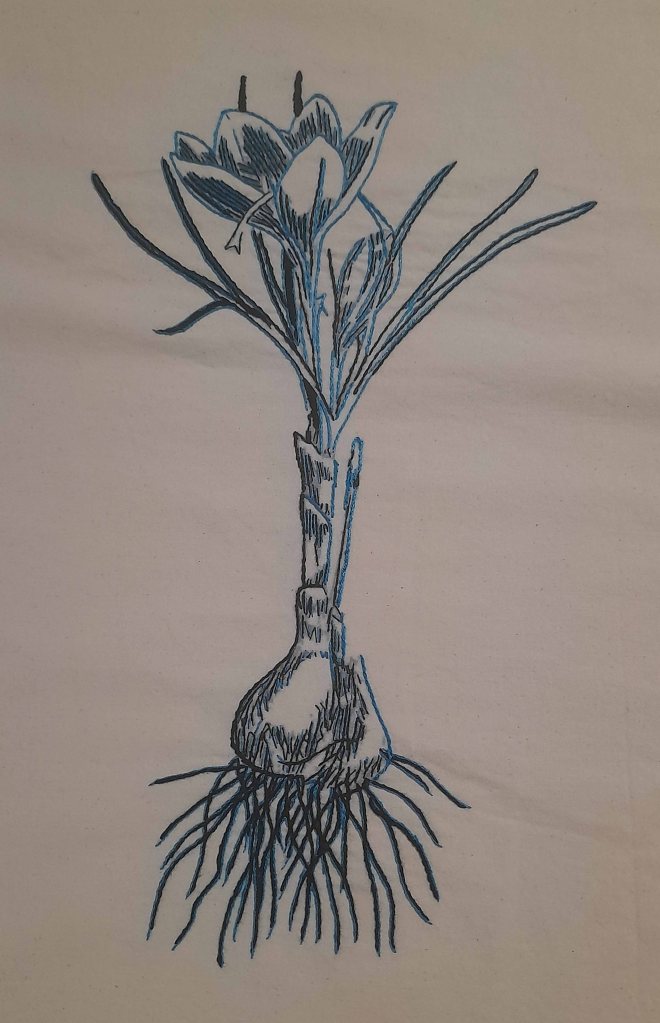

Marwa Arsanios approaches plants through a research-based, almost taxonomic lens. Pictured here is a detail from a series of tapestries shown at her 2022 exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms in London, created in collaboration with Syrian women and activists in Northern Syria. The blue threads, while disrupting natural realism, beautifully highlight the plant’s intricate details and layers of meaning.

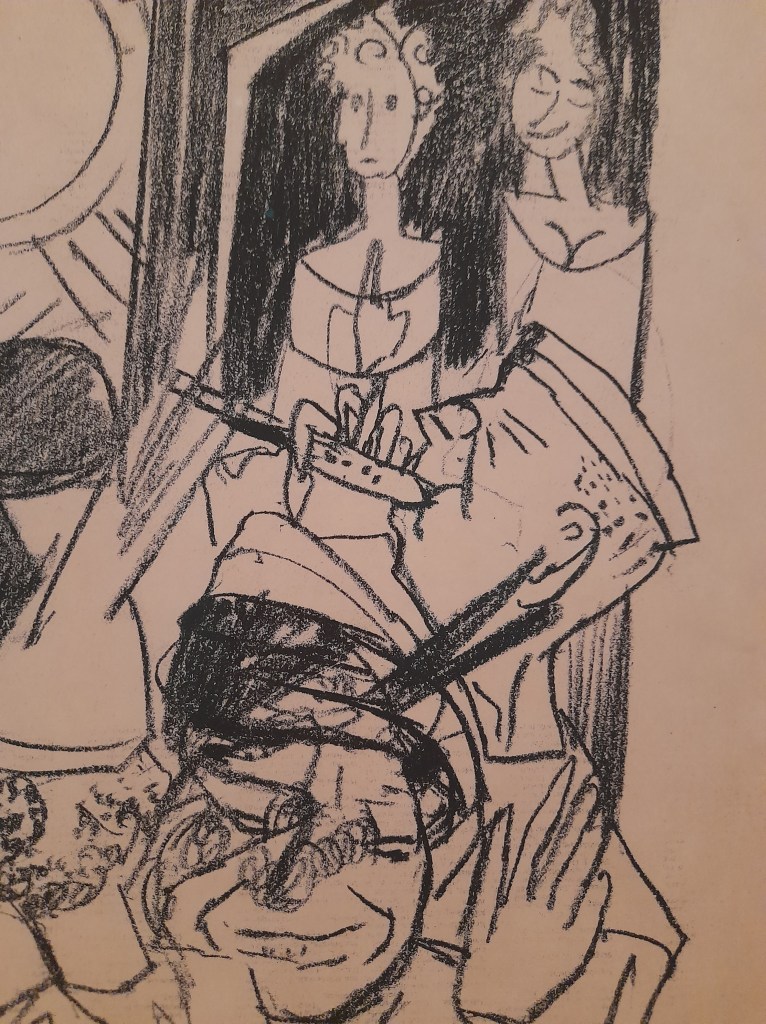

I spent a long time observing George Grosz’s charcoal drawings displayed at the MoMA in New York. In the complexity of his compositions, the German artist captured, with remarkable intensity, the postwar world around him—portraying both the beauty and the misery of the society in which he lived. It is striking to see the physicality of the charcoal lines on paper, where every mark reveals the immediacy and material presence of his gaze.

Perhaps one of the most extraordinary artistic projects I have ever seen. In his trilogy on the Crusades told from an Arab perspective, Egyptian artist Wael Shawky often employs puppets of his own design. In this photo, taken at his exhibition in Leuven, Belgium, are the stunning glass puppets crafted by Venetian artisans following his drawings—true masterpieces of color and fragility, where storytelling, craft, and history beautifully converge.

Mona Hatoum, Hot Spot, seen in a gallery in Berlin. The globe appears as a cage, its metal frame forming prison-like grids. The red neon outlining the continents evokes a sense of violence and unrest, yet I feel that the absence of political borders also suggests hope—a vision of a world without frontiers, suspended between tension and possibility.

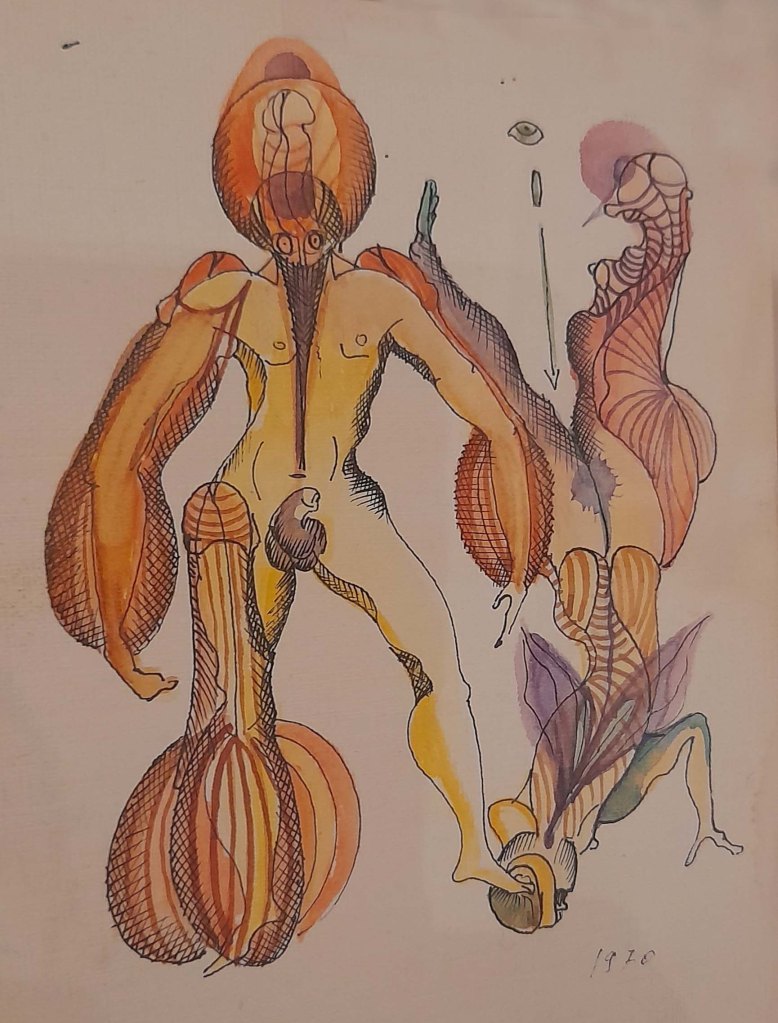

In 1970s Beirut, Juliana Seraphim created extraordinary watercolor paintings. This small-format work, which I photographed at an exhibition on Beirut at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, reveals her surreal, dreamlike world: phallic shapes intertwine with fairy-like figures, producing a striking tension. The precise black lines that define the forms testify to the artist’s remarkable confidence and mastery of her craft.

I saw this abstract work by Samia Halaby at an exhibition at the Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut. The artist herself attended the opening, despite having the flu and being nearly ninety years old. Her long career stands out for its deep political commitment and activism, intertwined with an exploration of lyrical abstraction through painting and pioneering digital art. I was profoundly moved by her presence and the strength that radiates from both her work and her words.

During Art Basel 2018 in Switzerland, I discovered the incredible sculptures of Pierre Huyghe. These works combine monochrome human figures with a head that is an actual beehive, alive and inhabited by a colony of bees. This fusion creates a unique relationship between art and nature, human activity and natural process — a living dialogue that, when placed within a lush green environment, gains even deeper ecological poetry and meaning.

I first encountered the works of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas at the incredible Polish Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, and later that same year at documenta 15 in Kassel. In Kassel, she presented a series of stunning tapestries—collages of various fabrics—that reinterpret episodes from the story of the Holy Family, such as the Flight into Egypt, through symbolism and references to Romani culture, which are central to the artist’s background.

A work by Malawian artist Billie Zangewa, which I saw at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town in 2025. There, the artist presented a series of luminous tapestry collages, mainly made from silk offcuts sewn by hand. Through simple forms and a mix of vibrant colors, she creates portraits of everyday life and community scenes—subjects that inspire her vision—captivating viewers with both the compositions and the extraordinary material, which she handles with remarkable skill.