I have always been fascinated by art as a form of communication — and by the ways in which it is mediated. Today, digitization offers new possibilities to share and study art, expanding access to culture while opening new methods of analysis. Technology can deepen our understanding of artworks and the contexts in which they exist. In this page, I share reflections and projects that express this passion, which has also become an integral part of my professional path. Feel free to reach out if you’d like to discuss or exchange ideas.

There’s a photograph of the art historian Bernard Berenson that has always inspired me. He is leaning in close to a painting with a magnifying glass, examining its finest details. This was the ultimate method for careful analysis before technology could assist us. It might seem outdated today, given the tools we now have, but it reminds us of a passion for investigating the materiality of art—an attention that no technology can ever truly replicate. Every artwork possesses physical, chemical, and subtle qualities that can only be discovered in the original.

In a 1990’s interview [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq5Rfhz7OHA], Federico Zeri claimed that being an art historian meant training one’s eye and visual memory. For him, the work of scientific laboratories could only go so far; what truly mattered was connoisseurship — the eye, the personal visual experience. Zeri also noted that whenever he couldn’t see an original artwork, he preferred to rely on black-and-white photographs rather than color ones, never reliable. Listening to him, I can’t help but wonder what Zeri would say about today’s technologies: about artificial intelligence, capable of analyzing and recognizing artworks with astonishing precision (though not without errors), or about digital imaging tools that now reproduce color, texture, and materiality with incredible fidelity. I think there’s still much to learn from Zeri: above all, that we should never let our eyes grow untrained. Despite technological progress, the original artwork remains irreplaceable. Yet, it’s equally stimulating to imagine how technology might accompany the work of future art historians — as long as we maintain a critical gaze, aware that technologies themselves are not neutral but often carry political and cultural biases. In this sense, I’d like to mention Nouf Aljowaysir’s series Salaf, which explores how artificial intelligences sometimes reproduce biased perspectives and racial profiling — a powerful reminder that technology must always be observed and questioned.

Today, photography and modern technologies allow us to study artworks in ways that complement and enhance the human eye. There are countless examples, but one in particular fascinates me. The art historian Raffaella Morselli recently conducted extensive research on the painter Domenico Fetti. With the help of photographic experts, she discovered pictograms within Fetti’s paintings—subtle motifs created by manipulating the letters of his own surname. These clues to authenticity were revealed through a meticulous “treasure hunt,” using macro photography, contrast adjustments, and digital image processing. In this way, modern investigative technologies become a new magnifying glass, extending and enriching the careful observational methods pioneered by experts like Berenson, as discussed in the previous paragraph.

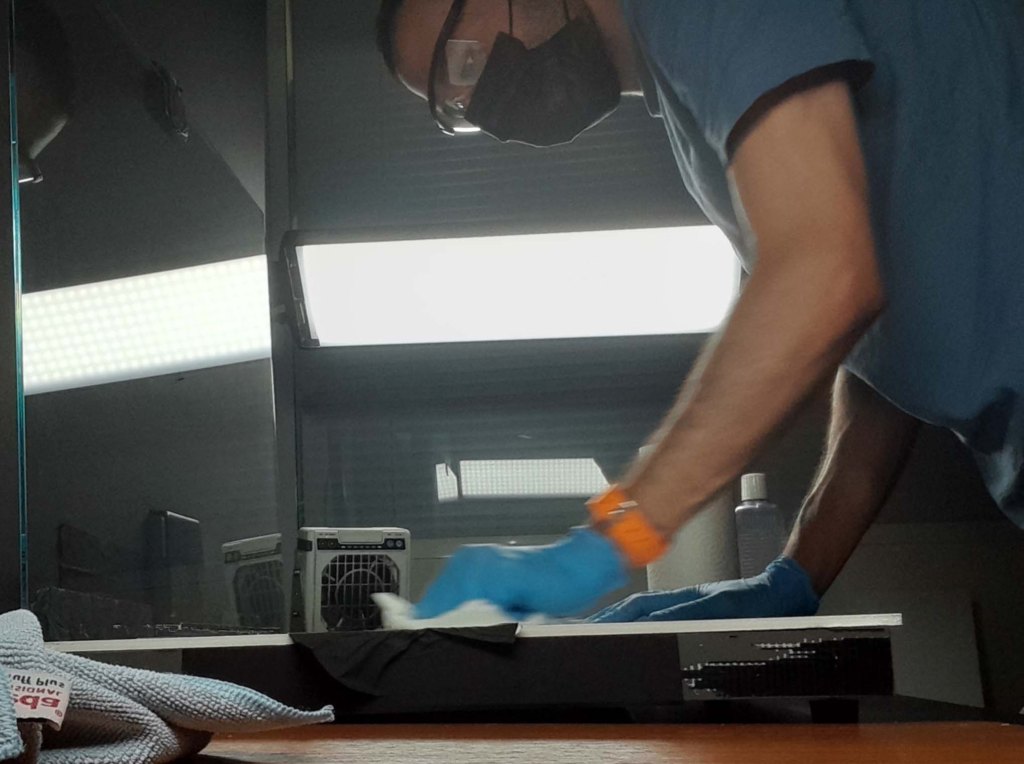

This photograph shows me working on the digitization of glass plate negatives in South Africa (see more on this in the Projects page). My focus here is on achieving the most faithful reproduction of the artworks possible through photographic technology. Capturing a precise image requires optimal conditions: careful attention to the angle of capture, focus, distance, resolution, and the final image quality. I am particularly interested in exploring the latest developments in these techniques, as they play a crucial role in making cultural heritage accessible and shareable, supporting both scholarly research and public dissemination.

In my current work, I focus on digitally reproducing artworks that exist only in analog or non-digital formats. One of the greatest challenges is finding the perfect light spectrum and making subtle adjustments to ensure that both colors and details are rendered accurately. For this reason, I spend a lot of time working in Photoshop, as shown in the screenshot beside me, so that each study can achieve the highest level of fidelity and precision. In the example, you can see a detail of a photo I took at the National Gallery in London of Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523).

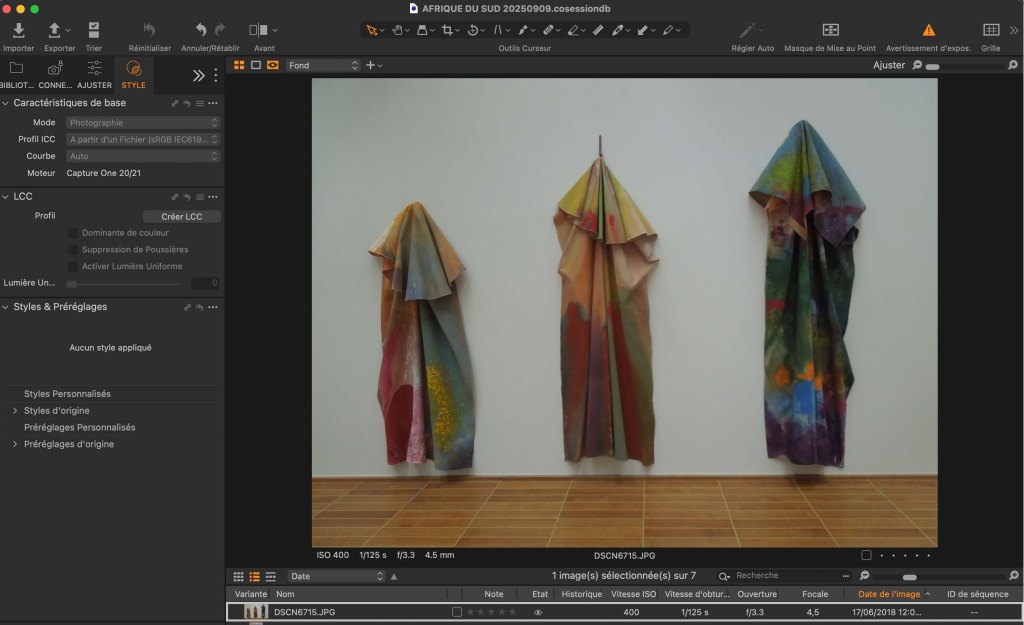

In my working environment, I have become accustomed to using a range of professional photography software, including Adobe Bridge, the Adobe Suite, Lightroom, Camera Raw, Nikon programs, and others. I work extensively with Capture One, which connects the camera directly to the computer, allowing to adjust photographic settings and begin live post-production. This workflow ensures that the digital version of each artwork faithfully reproduces the original’s physical and colorimetric properties. On the left, there is a photo in Capture One of an installation by Sam Gilliam that I photographed in Basel in 2018—an artist who works extensively with colors and their subtle variations, and the challenge is precisely to capture them perfectly in the photographs.

Through my work in digitization, I have learned the absolute precision required in this field. Working in an environment free of dust and contaminants, with meticulous cleaning using professional-grade products, and perfectly controlled lighting, is essential. Such conditions allow for the careful handling of large archives of artworks, ensuring that they remain unharmed and respected, while also enabling their faithful reproduction in digital format.